|

| One of Rusudan Petviashvili's works, showcasing her signature style |

Rusudan graciously translated the vivid creativity that lives within her not into her native tongue of Georgian, but into English for my own sake. I initially thought she likened her paintings to "parabolas", and immediately followed up asking if there was something mathematical behind her work. Indeed, her father's ancestors were physicists (search her surname on Amazon and you'll find a textbook), but she quickly corrected her word choice. She had meant to say "parables", as she illustrated not the structures and laws of mathematics but the fluidity and emotion of cultural narratives. Her eyes shone brightly as she explained further: "Reality is just put inside little fairy tales in order to be more beautiful."

|

| One of many vivid paintings in Rusudan's Tbilisi studio |

Her work is replete with not only themes but entire stories. There is not just motion, but activity. Rusudan herself is not only an artist, but something of a visual poet. Her words continued to expand upon her delightful perspective, as she said that "every person is like a universe", and she tried to capture the celestial qualities of humanity inside each figure of her paintings. As I looked around her studio, I could see that her art was absolutely rooted in human beings, yet not in so literal a sense that she was painting portraits or classical scenes. Instead, there seemed to be metaphors saturated in color, symbols endowed with human features. She elaborated on many of the symbols, some Biblical, and others simply fantasies of her own mind. Her eyes glowed with youth, a creativity that is as old as the artist herself.

Rusudan was born in another era, when the homeland she calls Georgia (or in her language, საქართველო - Sakartvelo) was known on maps as the Georgian Soviet Socialist Republic. Free thought and expression were not openly encouraged--parabolas, and not parables, were what geniuses pursued and paraded as the pinnacle of Soviet civilization Georgian culture was suppressed, but, as Rusudan recalled to me aloud, the Georgians would only go along with Soviet decrees while it was convenient. True suppression was something they would not tolerate, and actively resisted. All these years later, Georgian culture is flourishing, with its language, music, architecture, history, and many other aspects very apparent to any visitor. Georgia is certainly not Russified, nor a Soviet relic. Even at the height of the Soviet Union, there was something unique about Georgia--and Tbilisi at it's heart--that gave it a reputation as something of a "Russian riviera" that was known as the home of artists, composers, and poets.

|

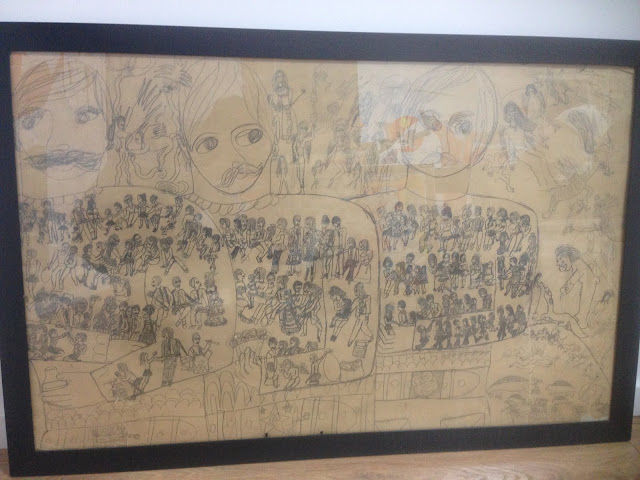

| One of Rusudan's first sketches, featuring perhaps countless small figures--she says she gave each one a story of it's own |

Georgian culture is part of what nurtured Rusudan into her career as an artist, but she also is a product of both an artistic family, of the influence of the Western world, and even the explicit encouragement of the Soviet Union. More than anything, she remarked, she is inspired by her own heart and soul--not by the works of others. Rusudan was sketching and painting from a very young age, under the guidance of her sculptor father and poet mother. By the age of six, she had made over 80 complex drawings. Two years later she was in Moscow, where one of her art exhibitions, scheduled to be two weeks long, ended up on display for three months instead. People came from all over the Soviet Union, in disbelief that they were viewing the work of a child. Some said the art resembled old Georgian manuscripts, but indeed it was Rusudan's own imagination and touch that produced such remarkable beauty. The French ambassador to the Soviet Union was one of her early admirers, and proposed that the Soviet government allow her to travel to Paris to showcase her art. For the Soviets, this was an opportunity to show the height of their people's art, and she quickly became not discouraged but prided. Eduard Shevardnadze, leader of Soviet Georgia, approached her parents in order to ask how he could help foster Rusudan's creative spirit; her mother replied that the best help was to refrain from bothering her.

|

| Another of Rusudan's earliest sketches depicting her tale of three giants |

Tbilisi was something of a Soviet Paris, Rusudan told me. This recalled my travels to other versions of "Paris"--Beirut, as the "Paris of the Middle East", and Buenos Aires as South America's equivalent. All earned these titles for their permissive, artistic, and progressive atmospheres at some time or other, but all had also lost that spirit in cataclysms and transformations. Tbilisi, however, had seen a different timeline. Tbilisi was a beacon of this spirit amid the austerity of the Soviet Union's other republics, and all these years later is still a hotbed of culture recognized by its neighbors. Nonetheless, Rusudan's life changed drastically when she left this "Soviet riviera" and went to visit Paris itself--not as a tourist, but as an artist. Her sketches became full fledged paintings, and her life as a whole became equally colorful.

In the Soviet Union, Rusudan told me, "everything was grey." To her the whole region seemed pale and lifeless, yet inside she felt a burst of vibrant color. "I had a feeling that I was in jail." The Soviets initially refused to allow her to visit Paris, instead suggesting another Soviet artist visit--but the French response was firm, insisting that it was Rusudan and her exhibition that they wanted to bring to France. Rusudan herself didn't participate in the politics of the art scene, but instead simply focused on her work. She looked to stand above the difficulties and conflicts posed by the rivalry of the Soviet Union and the West, and hoped to look inward for her inspiration. Human figures continued to dominate her work, more and more vibrantly. "A human being is a very special creation," she said dreamily. "He can do, he can receive, he can reach everything--can be perfect, can be cruel, can stand above or below himself. I love people who stand above."

Her first impression of Paris, after visiting as a 12 year old girl, was how colorful everything was. She said it felt free and like a true home--a feeling she is now acquainted with after so many subsequent visits there. When she returned from Paris, Rusudan had difficulty explaining to her peers what it was like. She went back to her work, and continued to excel. The year was 1980, and it was still a decade before she would find the same colorful freedom blossoming in full in Tbilisi. During those coming years, she browsed her father's books in admiration of other artists, finding herself in particular amazement of Impressionist paintings. Other influences included Egyptian hieroglyphs, which have a vague resemblance to the elongated figures in her forthcoming paintings. She also enjoyed the work of Georgian artists, many of whom had been renowned internationally in years past, but she saw their work as a different flavor entirely and not of great influence to her own aspirations. Her own methods drew strongly from Impressionists but with a twist--rather than relying on color as the basis of her pieces, she relied on the lines. She began to illustrate with unbroken lines, never lifting the pencil from the paper, before painting on her color.

|

| Rusudan's paintings express fantastical scenes replete with color and emotion |

In a sense, Rusudan's method can be compared to a writing technique called "stream of consciousness." When I asked her if this was a legitimate comparison, Rusudan was puzzled--she hadn't heard the phrase. To me it evoked the writings of Jack Kerouac, I explained. His most recognizable work, On the Road, was written over a three week period on a continuous scroll of paper. Many parts of the book feature what some would call run-on sentences, where thoughts continue at length without punctuation. To many, it was an artistic signature, and I could see the same in Rusudan's method in some vague sense. She had never read Kerouac's work, but seemed interested in his own themes of freespirited travel, and exploring the humanity of post-war American culture. Her appreciation for writing is as innate as her talent for visual art, and I could see the curiosity light up in her eyes.

Her own experience with writing involved two landmark projects. Rusudan cooperated with a French-Georgian writer, Gastogne Buachidze, illustrating his 1989 French translation of the Georgian epic poem Le Chevalier à la peau de tigre (The Knight in Tiger's Skin). The book has long been out of print, but is still quickly found on Amazon's French website--and features Rusudan's illustrations that attempt to capture entire chapters in a single image. I tracked down a copy, and found that the detail is indeed remarkable. The poem itself is of national pride in Georgia, authored by Shota Rustaveli--whose name now graces one of the most beautiful and well-known streets in Tbilisi. To illustrate such a national treasure was a great privilege, but her later landmark project was even more moving.

In the 1990s, the Georgian Orthodox Church commissioned a 100 kilogram Bible, each page made from calf's skin. For three years, Rusudan worked on 60 miniature illustrations for this Bible, putting aside all other work. From 9 in the morning until 7 in the evening, this was her focus. It all began when she visited a close friend of hers, a nun, and came into conversation with the Patriarch of the Georgian Orthodox Church. The Patriarch, leader of the church, asked Rusudan if she was familiar with the Old and New Testaments, as well as the medieval versions of the Georgian alphabet. Indeed, she knew two versions of the medieval alphabet in addition to the modern Georgian alphabet. Rusudan saw this as a special calling--she had fallen into a depressive mood following conflicts in post-Soviet Georgia and the breakaways of Abkhazia and South Ossetia. She was psychologically exhausted, but saw promise in such a project. After three years of work, she felted changed, but couldn't verbalize to me exactly how. In the end, it is an emotion perhaps best seen in her continued work.

|

| A personal touch on the wall of Rusudan's studio |

The themes in Rusudan's work are positive and hopeful, but not without a darker side. Many scenes she paints feature beasts that are undeniably ugly. "Envy has no face," she said. "When I want to express rudeness, there is an ugly face with it." Nonetheless, these darker elements are part of the greater whole. Her paintings, which shows extremes as mentioned before, overall emphasize the concept of harmony. "Life is so," Rusudan remarked, her eyes gazing around her studio. She described evil and bad intentions as plumes of smoke, covering large spaces but in reality having little substance. "Good things are like honey--little, and sweet."

She directed me to one of the most unique paintings in the room--a sketch, but far more advanced than the earliest paintings of her youth. This one was of Noah's Ark, and, like her other works, truly presented a story. One critic had counted something like 800 individual figures in the scene, but Rusudan shrugged it off--she wasn't sure how many were really there, as she simply let the scene flow from her imagination. Crafted when she was 12 years old, around the time of her first trip to Paris, this one was now valued at one million dollars. I stood in front of it cautiously, less taken aback by the price tag than by its detail. It is infinitely intricate, with detail to the millimeter. It features a ship floating not on the sea, but above the sea, with sails like fish scales and bird feathers. It resembles also the variety of patterns in the plume of a peacock, or the patchwork of a quilt. In the scene one can spot a sleeping beauty hanging in a basket, twig-like oars, proud masts, fluttering birds, leaping fish, yelping dogs, blaring trumpets, and a single disk of sunshine with a red pupil like an eye with rays. There are bearded men with chests like roosters, women with cascading locks of hair, three rafts, and opposite the sun hangs a crescent moon. It's able to be read, examined, and explored.

|

| The intricate painting of Noah's Ark, straight from the mind of Rusudan Petviashvili |

Across all of her paintings, Rusudan has several persisant images and themes. There are scenes of people who love one another, not outwardly but inwardly such that they create their own souls. Wings on women show their yearning to fly, despite being tethered to a man at the time. Birds on the heads humans, looking to the east, serve as a symbol of positive and inspired mindset. A bird in the hand, however, indicates poetic nature of the depicted person, and the moon behind the head--like a halo--shows a man who is a gentle dreamer. Boats carry problems, while angels come to save those in the boats. Some paintings feature only a single sun, while others have many. A large one indicates a brilliant and shining person underneath it. Some of the figures have two faces, in an almost Picasso-like fashion, showing that they wear a mask. Humans, she explains, act as one person but inside are another. Anger can be a mask for misery, kindness a disguise for strictness. Painted rivers flow by like life itself, unobstructed and always in motion.

Rusudan's dreamy world is alive and well in her paintings, and her intent is express her true feelings--especially that of love. She was 22 years old when the Soviet Union fell, and all these years later her artwork has continued to flow despite ups and downs. I asked her what goals and dreams she still has, but she shook her head, stating: "I never dreamed. I don't like to dream. No... I have a vision." I was puzzled, and pressed her to elaborate. She continued: "In dreams, things never really happen, they happen already in dreams but not reality." She smiled. "But to wish is good--you are gathering your strengths to make something."

|

| A work in progress |

Rusudan's words left me inspired, augmenting the power of her artwork. She continues to be recognized in Georgia and across Europe for her unique style and powerful message, and undoubtedly will continue to paint for the rest of her days. Her work can be viewed in the National Gallery of Georgia in Tbilisi, at Rusudan's Gallery Art Cafe in Batumi, Georgia, as well as on her official website. Each piece is intricate, beautiful, and inspiring. More of her work can be found in collections and exhibitions throughout Europe, and hopefully will continue to gain renown as a pinnacle of modern Georgian art and a colorful expression of human emotion.

I asked Rusudan for her wishes, rather than dreams--what she wished for her country that she had watched transform over all these years, and for herself who had also transformed. "For Georgia, I wish her to be independent, united, filled and overflowing with kind, good Christian people. Kindness is the main thing, to be a special country and have her place in the community of the world. Everyone should know of Georgia's kind influence, and that this kindness is always shining toward everyone." She took a deep breath, and continued: "for myself: my aim is to be on a very high level, to be always truthful, have strength to be truthful, to be always filled with love, never love the inner feeling of love. Love strengthens, losing love is exhaustion. Love in and of itself, inside of the self."

|

| The door to the outside, a last glimpse of art before I concluded our interview |